Hi All!

Two admin notes. First, I’ll take a break from blogging until early January. Second, all the pix that I threw into this were from open source internet, none of it is original by me. If someone has an issue or wants specific credit contact me and I’ll update accordingly.

OK, I asked you guys for questions about FPV drones and drones in general and unsurprisingly a lot of what you asked forced me to think harder than I was planning. Hopefully the answers are useful.

Rereading everything, it sort of seems like I’m declaring all weapons systems are obsolete except drones. No I’m not saying that. The future will tell. But the trends and numbers I’m kicking around, really look real to me.

Tom Cooper

Q: Exactly how much of Ukrainian FPV-production is really paid by the government (no matter what agencies)?

A: My simple answer guess would be “By money, my guess, about 80 percent. Maybe more. By individual unit production, somewhere between one third and one half of all aircraft, and I’m inclined towards the lower number.

My more detailed answer breaks up the production into types. At the top of the drone feeding chain are the long-range drones used for strategic strikes. This is 100 percent run by the Ukrainian government, and for the most part it is outside the hands of the military, i.e., it’s HUR or SBU. The degree to which foreign states are involved is unclear and it seems to vary from type to type. Past “there is clearly some foreign involvement” I can’t say anything about degree. My guess is somewhere between $50-$150 million gets spent every year, somehow, on this category of weapons. Whatever the figure is, the money has to be coming from a state and taxpayers.

At the bottom of the food chain are the humble FPV drones. The Ukrainian government right now is claiming about 100K drones of all types are manufactured every month and it’s no secret that by aircraft count the overwhelming majority are this one-use kamikaze aircraft. I am told that existing, registered drone units do receive government-manufactured FPV drones.

However, this is widely viewed as an additional source of drones complementing manufacturing chains that largely grew up on the back of efforts of on-the-ball brigades with a strong leadership that had the resources and inclination to figure out how to improve fighting capacity by increasing drone capacity. This was absolutely bottom-up, organic development. The only top command input was, literally, not to actively seek out and shut down budding drone operation sections because that wasn’t SOP at the time.

This was paralleled with civil society operations, volunteers and activist citizens for the most part, who usually had some personal link to a combat unit that either had drones or wanted them. Some are pretty big, like United24 (which has some government sponsoring and blessing) but most are just outside government. All those supply chains have developed over time and from what I see FPV production and development right now is still overwhelmingly what some would call cottage industry where the entire production process is outside state management and control.

My personal guess is that four out of five FPV drones reach combat only do so because civilians not employed by the government were somehow involved, and further, that that mass of aircraft probably accounts for 90 percent of all the drones that make it to the battlefield.

My opinion, we might not be seeing a military technology revolution on the level of a repeating black powder rifle or a machine gun, but we might.

Jim Parton

Q: Some Ukrainian friends said that Russian “mother” drones that drop smaller ones were a problem and that Ukraine doesn’t have them. That was a couple of months ago. Yesterday I read that Ukraine now does have them. Any information on this? Drones are a rapid arms race. Is it one where Ukraine stays ahead, by and large?

A: Both sides have experimented with mother ship drones at least since 2023. Their use is not widespread. My understanding is that, the operators seem to think that if your drone can reach a target area, all in all it’s usually more effective to tote a dropped explosive or a camera, than a drone carrying less-capable version of the same payload. Sometimes “mother ships” are used as repeaters to boost signal strength in an area, but unsurprisingly going somewhere and then putting out a really strong signal can get an aircraft shot down. My guess would be that your friends hadn’t heard about the Ukrainians using mother ships where they were because for whatever reason the Ukrainian drone operators in that sector weren’t bothering with it. But the technology has been used by both sides for some time.

Roy Cauldery

Q: Hi Stefan

Robert Magyar has recently mentioned a huge drop in drone effectiveness for both sides.

Down to as much as between 20–40 % success rate.

How are the drone teams you interviewed seeing that in their sectors by comparison?

Are the drone builders now favouring fibre optic cable flown type products?

A: To take the second question first, fiber optic cable is absolutely seen as a tactical solution, but, it’s not free. I’ve seen reports of spools reaching 20K and costing $1000. I’ve got one source telling me it’s possible to find the spool for $200. There are savings in weight because you don’t need antennae and jamming protection. Still it’s extra cost, and meanwhile conventional FPVs are cheap. Plus wire-guidance isn’t perfect, if it hits water you lose your signal and your drone is lost, caught in a tree same thing etc. etc. The bottok line is that you could deliver four or maybe even six conventional FPVs at a target for the price of one wire-guided FPV, and although a better weapon in a lot of applications a wire-guided FPV is not the best weapon in all applications. In any case it’s not in wide use right now.

As to success rates, 20–40 percent is in a tough environment with a lot of jamming and the enemy aware of the drone threat and practiced at countering it. As we have seen over and over, green units and poorly-led troops have little idea how dangerous drones are and can take very serious losses before they start learning. In those engagements drone, NATO, even well-led NATO units, I think, would get cut up and very possibly reduced to ineffectiveness if put into a battlefield in Ukraine right now.

Mike O’Brien

Q: I’ve seen FPV kamikazi drones target individual Russian soldiers. I’ve always wondered how cost effective that is? Also, is Ukraine developing Hunter-Killer drones armed with automatic weapons or rockets to attack Russian drones?

A: Yes, Russian drones are hunted by Ukrainian drones, but not with automatic weapons. The main tactic these days is ramming.

I’ve been told that the rock-bottom, no-profit-margin price of an FPV drone these days, without the explosive, is $330. A general rough number usually used by operators taking into account the price of the van, equipping the operators, the control equipment etc. etc. that goes into the strike, is that a single boom in the vicinity of the enemy costs around $500. Considering the Russians are paying $20,000 bounties to get a man to volunteer to fight these days, never mind the cost of equipping him and arming him, using a single FPV to kill or wound a Russian soldier is an excellent exchange from the Ukrainian point of view, even if they expend four or five drones to get a hit.

Another way to do that math would be to compare the cost of a guided FPV drone, to the cost of an unguided 155mm shell. Neither munition will guarantee a wounded or dead enemy soldier, but, if four or so are sent towards a known enemy location, it seems like the expectation that should be enough to get a hit on a single targeted individual is about the same. Right now, Rheinmetall is selling 155mm shells at about $3,200 a pop. Yes the shell is more destructive and it can’t be jammed, but it’s not guided and its launch system is a massive artillery piece costing $10–15 million, an observation drone, plus a trained crew and the logistics to support the gun.

To launch an FPV drone you need about three skinny guys, a van, a controller, an observation drone, and however many more FPV drones and energy drinks you can stuff into the van. All in all using a drone to attack enemy infantry is probably at least ten times cheaper than trying to do it with artillery.

James Touza

Q?: Drones and what they do just freak me out, and I don’t even live in New Jersey. The modern battlefield had enough terrors without drones, now it’s unimaginable to me how both sides function. When AI is further developed and incorporated, the battle space we knew may not be possible.

A: This wasn’t a question but I’ll springboard off that comment to hit again the point that I don’t think other militaries have a good understanding of how lethal and widespread massed FPVs over a battlefield have become. Yes, I know you can read in NATO doctrine how they understand and are taking steps. But in any kind of face-to-face battle between a combat unit that has lots of FPV drones and knows how to use them, and a unit that is up against them for the first time, my expectation would be that the inexperienced unit would be cut to pieces. It’s a war where the entire sky is a permanent danger area to individual soldiers, for both sides. You are less worried about artillery than you are about drones. The last time artillery wasn’t the biggest danger on a European battlefield was probably sometime during the 1700s.

Fabio Bulfoni

Q: Hallo.

I collected a few questions within “my” network:

(1) — how does it begin? Operational requirements from units or decision from manufacturer?

(2) — FPV drones are single use: how deep is the search of cost reduction?

(3) — About the electronics: do they install circuit board from existing manufacturers, like Rasperry and Arduino, or are they producing circuit boards, too?

(4) — In percentage, how much is delivered to units by MinDef and how much is exclusively crowd funding?

(5) — does training plans of pilots exist or are pilots trained “by experience”?.

Thank you!

A: I’ve numbered your questions.

1. On how they’re designed, it’s driven from operators, they say what they need and the producers try and give it to them. It can be tweaks as minor as the angle of an antenna. The operators say “we need to do this, please make the drone capable of that”, and then the manufacturers try and meet those criteria. A problem is, of course, different users will inevitably have different criteria, plus this is war not Amazon, and it’s pretty inefficient to have a muntions supply chain that might have to tweak a product to suit an individual consumer every time the consumer decides he wants something better. But for better or worse, if on the FPV/tactical drone side, it’s bottom up. It’s operators working with unit technicians to solve specific problems like how to get more range, carry a bigger payload, fly higher, be more resistant to jamming etc. All the innovation it seems to me is starting with a specific battlefield problem that the guys on the ground see a need to overcome.

On the strategic drone side the impression I get is that the state goes to individual manufacturers and says “Can you make this/meet these criteria”, and when a manufacturer makes a successful pitch that it’s possible, a production contract is signed. I strongly suspect — but have no proof past past production capacity of the Ukrainians that we know about — that if there is western tech/advisors involved that’s where the assistance is going.

2. On cost I really can only talk about FPV drones. Here there clearly has been a classic manufacuring “race to the bottom” where manufacturers are competing on price first but the demand is for a level of quality that precludes the very lowest price. It’s not like there are one or two drone parts manufacturers, there appear to be hundreds of companies listed in AliBaba or similar that can manufacture parts. After three years the Ukrainians seem to have a pretty good understanding of the manufacturers out there — although there always can be more to be found. I got shown a web site that is kind of like a Yelp for Ukrainian drone manufacturers, one page for instance is companies producing motors with reviews and comments by customers. So I get the impression that prices now are just what the market sets by competition and the only way to reduce them is with a big order.

3. On electronics, I was told “almost all” electronics are produced outside Ukraine BUT part of the wide net by sourcing is buying for instance circuit boards that aren’t 100 percent suitable, and then modifying them in shops in Ukraine. Nowhere did I get the impression that it was technologically impossible for Ukrainians to manufacture electronics themselves, they seemed very confident they had the skills, knowledge and experience to do that. The point was, at this point, it’s cheaper and easier to source them from abroad. There may be big costs involved in setting up electronics production in Ukraine that I don’t know about.

4. I made my guess of what percentage of the FPV drones are crowd-sourced and what percentage are government-sourced at the top.

5. Training at this point is at the unit level, that is brigade. The UAF has created a drone troops branch and it’s reasonable to expect that over time that branch will train and feed operators into the combat units, but, as of this writing that’s the plan. Pilots get trained at units and for the most part they learn on the job. As you might expect, the units with the resources to acquire drones via volunteers are far more often to create dedicated drone training and it’s the usual suspects, 92nd Mech, 3rd Assault, the Marines, Kraken, the Special Ops guys, Azov, Khartiya, and so on. They are also far more likely to have in house manufacturing.

Cliff Volpe

Q: What percentage of Ukraine’s war expenditures is allocated to drones and drone warfare?

A: Great question, the direct answer is I don’t know. However, if we speculate based on what we know about ongoing production, the north end value of all the drones that Ukraine manufacturers in a year — exclusive of R&D — can’t conceivably be more than about $2 billion. A more responsible guess would be less than half that. Further, as noted above, government war expenditures on drones produce only a portion of all the drones that get built.

If you want to look at the macro numbers and do some guessing, rough figures, Ukraine received about $150 billion in real military assistance during 2024. Estimates of domestic military-related expenditures bounce between $12–50 billion, depending on what’s counted.

When you look at the cost of all the drones, it’s immediately clear the precise figures aren’t really important. The real takeaway is that in terms of weapons tech drones are quite possibly the most effective means the Ukrainians have of destroying Russian fighting capacity, and if they are not then they for sure are close second to artillery and long-range missiles. But the amount of money spent on Ukrainian drones, all sources, cannot be more than one percent of all the money that is spent on Ukrainian military capacity.

Most field guys estimate between one-third and one-half of all Russian casualties these days are drone-caused. If this were a computer war game simulation, the obvious thing for the Ukrainian player planning war production to do would be to stop manufacturing big ticket weapons like surface-to-surface missiles, and logically even tanks and artillery, and just create UAV brigades so that a Ukrainian brigade general can pick a sector of the front and put 1,000+ FPV drones into the air every day for a month, and to his right and his left, there are other brigade generals doing the exact some thing in their sectors. By the numbers, which are driven by the drones’ low cost, no army on Earth could stand an onslaught of precision-guided munitions like that.

Jacob Dinneen

Q: Can you give an overview of drone warfare at some point or give us a good overview? Distance, types, payloads, flight times, how they avoid or overcome jamming, and tech advancements since 2022. Stuff like that.

A: Honestly the subject is changing so fast that a lot of what gets written becomes dated really fast. I have to write on drones in this war for my day job all the time so if there is a single source of information on that I’d love to see it.

I do have a standard anecdote I tell about how far drones have advanced in this war is that in July 2022 I went to the front with a drone unit and state-of-the-art at that point was a Mavic modified to carry a single VOG mini-grenade, which was the strike element, and a little camera drone that did observation. That was their entire aircraft fleet. Five km. was about maximum range. Only good weather. That same unit now has four strike drone sections, a big long-range observation section, a single ground drone section, an electronic warfare section, and “fighter” (shoot down the other guy’s drones) section. They manufacture their own FPV drones and repair pretty much everything. They have munitions that blow up on contact, munitions that are command-detonated and mines that react to movement nearby. They have all manner of clever tactics. Leave the drone on the ground awhile to save battery power. Knock down the Russian drone and then fly friendly drones on that frequency. Smoke grenades inside a bunker and mines waiting for the enemy infantry when it’s forced to the surface to get oxygen. And that’ s just a small piece of how far the Ukrainians have come.

Thomas Brayford

Q: Hi Stefan, always enjoy reading your analysis. Keep up the good work. How significant is the announcement that China is cutting off drone supplies critical to Ukraine’s war effort? Can Ukraine adapt to this new reality? And can drone technology really be decisive in this war and tip the balance in Ukraine’s favour?

A: As noted above, on the sourcing, the impression I get is that manufacturing of drone parts or components that might be used as drone part is pretty widespread and that, along with skills of places like Dubai and Hong Kong have in evading sanctions, seems to make the Ukrainians reasonably confident that the Chinese might make drone component acquisition a bit more time-consuming or expensive, but they can’t stop it, they don’t control their own economy that tightly and the world is happy to make money transshipping Chinese goods.

In terms of decisiveness, absolutely. It’s already happened. From Jan-May 2024, the US stopped all arms shipments to Ukraine, which included the absolutely critical item artillery shells. At the same time European allies were unable to organize increased shell manufacturing of their own. As this happened, the North Koreans sold the Russians a giant number of artillery shells, something like 3 million rounds. The net effect of this was to leave the Ukrainian artillery absolutely unable to handle the Russian artillery because the Russians could fire 20 rounds to every one the Ukrainians had.

The Ukrainians filled that gap, imperfectly, with FPV drones. There was ground lost in the Donbas but there were no Russian breakthroughs or collapses of Ukrainian defenses. Indeed, by mid-2024 Russian combat losses were at all time highs. It is simply a factual statement to say that the continued existence of the Ukrainian army as a coherent fighting force, in the first half of 2024, is a direct result of the Ukrainian army’s decision to be the first army in history to replace artillery with drones on a large scale.

(As an aside, there are western analysts that were really mad at the Ukrainian army for losing ground at the time because, as they saw it, the Ukrainian army was armed with a lot of NATO cannon that shoot further or more accurately than Russian cannon, so if the Russians advanced it meant the Ukrainians were incompetent, or just stealing NATO assistance, or both.)

Mihály Oláh

Q: Hi. As for estimated Russian losses posted by https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua I would like to ask if you have any public info about why russian artillery losses have fallen recently. Thank you.

A: The general opinion of people I talk to on the front is that there are two factors. First, the Russian artillery is not out of ammunition but its shell supplies are more limited than before, this because of having shot off a lot of the North Korea-provided shells and also because of Ukrainian long-range strikes against Russian ammunition depots. Russian guns that shoot less are coming into range of Ukrainian drones and missiles less often, so, less Russian artillery gets damaged and destroyed. The other aspect commonly reported is that the density of Ukrainian observation drones in the 15–30 km. zone behind Russian lines is increasing, this because of increased production and foreign supplies. This has made it more dangerous for Russian artillery to move into a range capable of reaching Ukrainian positions, and so, has reduced Russian attempts to position artillery where the Ukrainians could reach it.

Max Rottersman

Q: I’d love to see a breakdown of sourcing risk for each part: battery, motor, rotor, controller board, GPS module, camera, wifi module, carbon parts. Especially the the chips on the controller board. Does Ukraine get the same access to parts from China as Russia? Are DJI drones sill much better than home-built, or has that difference gone away. I am SO looking forward to your story!

A: I would love to see something like that too but I haven’t. The Ukrainians told me carbon parts, rotors, batteries and motors are simple to manufacture domestically and in smaller quantities already are. Camera I just don’t know, but, already we have seen the Russians use off-the-shelf DSLR cameras in some of their observation drones, so my guess would be the consumer photography industry which really isn’t China-dominated would be able to fill any need the Ukrainians could have. GPS, controller board, wifi module to a lesser extent are the same deal, there are other sources besides China, it’s just that China is the biggest and most configured to small batch export.

On DJI drones the humble Mavic is pretty much the standard tactical drone suitable for observation or reconfiguration to light bomber duty, because it’s reliable, relatively cheap, and everyone knows how to operate one. Mavics are considered much too expensive and well-built to throw away as an FPV weapon and too low-capacity for serious bombing missions. But outside the Mavic, the Ukrainian strategy seems to be buy close to your need first, and then over time work towards building it yourself, or, buy and modify to suit your need.

William Tracy

Q: When someone comes up with a new FPV design, or improvement of an existing one, how long from concept to battlefield?

A: Excellent question. The answer is of course it’s variable depending on what’s wanted and how complicated it is, and what kind of resources are available to get the new drone or doohickie aboard the drone functional. As an example, the drone builders I talked to told me that after an initial batch the unit operators came back with a request for the antenna to be configured at a different angle and the part where the battery gets strapped on to be cut differently, so that more kinds of batteries would fit on it. These minor changes to the production process took about a week. Same group, different example, from the moment of “Hey, we should build some drones, I wonder how we could do that?” to the “Thanks, your combat drone flew its first mission” took about three months.

A final example was that the war started in Feb. 2022 and Ukraine had no strategic drones of its own manufacture, at all. By June 2024 the Ukrainians were sustaining long-range drone bombardment of Russia with 100–200 aircraft a month and quantities increasing, and they were about to field their first jet-propelled long-range strike drones.

Richard “Cookie” Cooke

Q: Hi as per the drones what is the time line from conception to getting dropped in target

A: As above, in the example I encountered it was three months. The guys told me that if they didn’t have day jobs and someone were to have fronted the money it would have been half that.

Etienne Paresys

Q: About your next article on drones- would be great to have some stats on Druk Army. Most of the jobs are aimed for drones.

I am a member now based in UK. Known nothing about 3D printing before but already printed 20kg and sent many parcels with bombs and drone specifics parts. Looking forward to your article

A:I can’t say much about DrukArmy beyond what I know from their own publicity materials. But at minimum they are I think a great example of how drones and drone manufacturing are developing on the Ukrainian side in this war. Grass-roots and crowd-sourced.

Thanks so much, Stefan, for sharing all this. Some thoughts:

1. This is so outside the box that almost no commentary about the war incorporates its lessons. And the textbook is very much still being written, as you emphasize.

2. As a result, the Ukrainians seem far more resilient to loss of support today than they were. And with the stories on manpower issues and running out of hardware like gun tubes for the Russians, I am hopeful that the Ukrainians might hold out through a period of low international support long enough for the Russians to collapse.

3. To that end, my donations to private support for the war are already personally painful, but may need to increase in 2025.

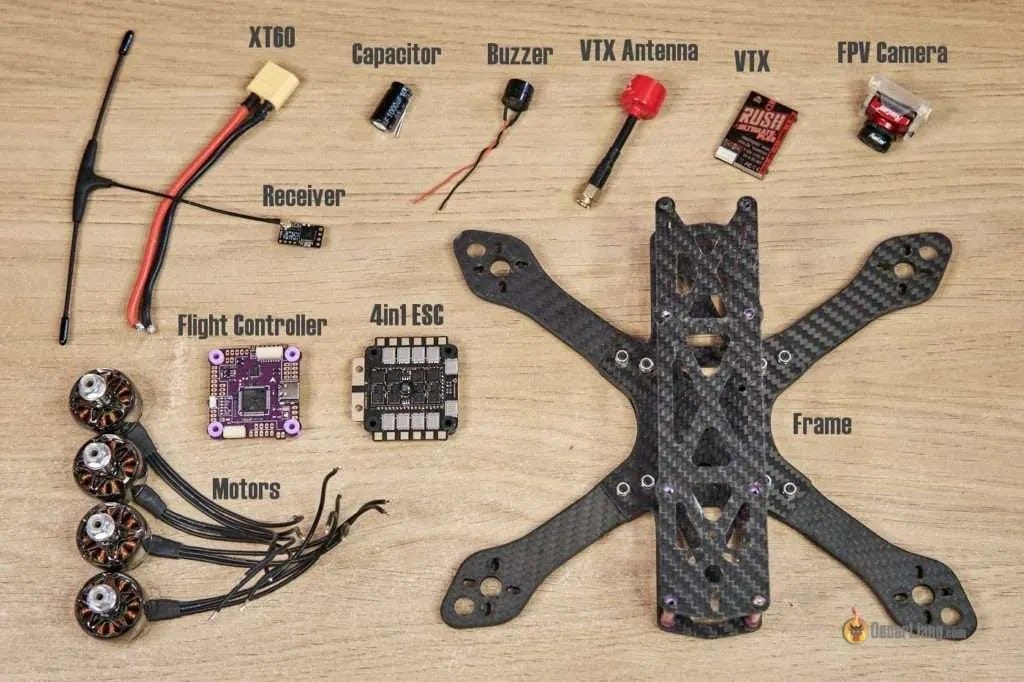

4. Despite how serious all this is, when I read this and see the parts photo, I can't help thinking that it would have been so much fun to have access to drone tech 60 years ago, when I was a kid.

Thakns. This was very interesting and very useful.